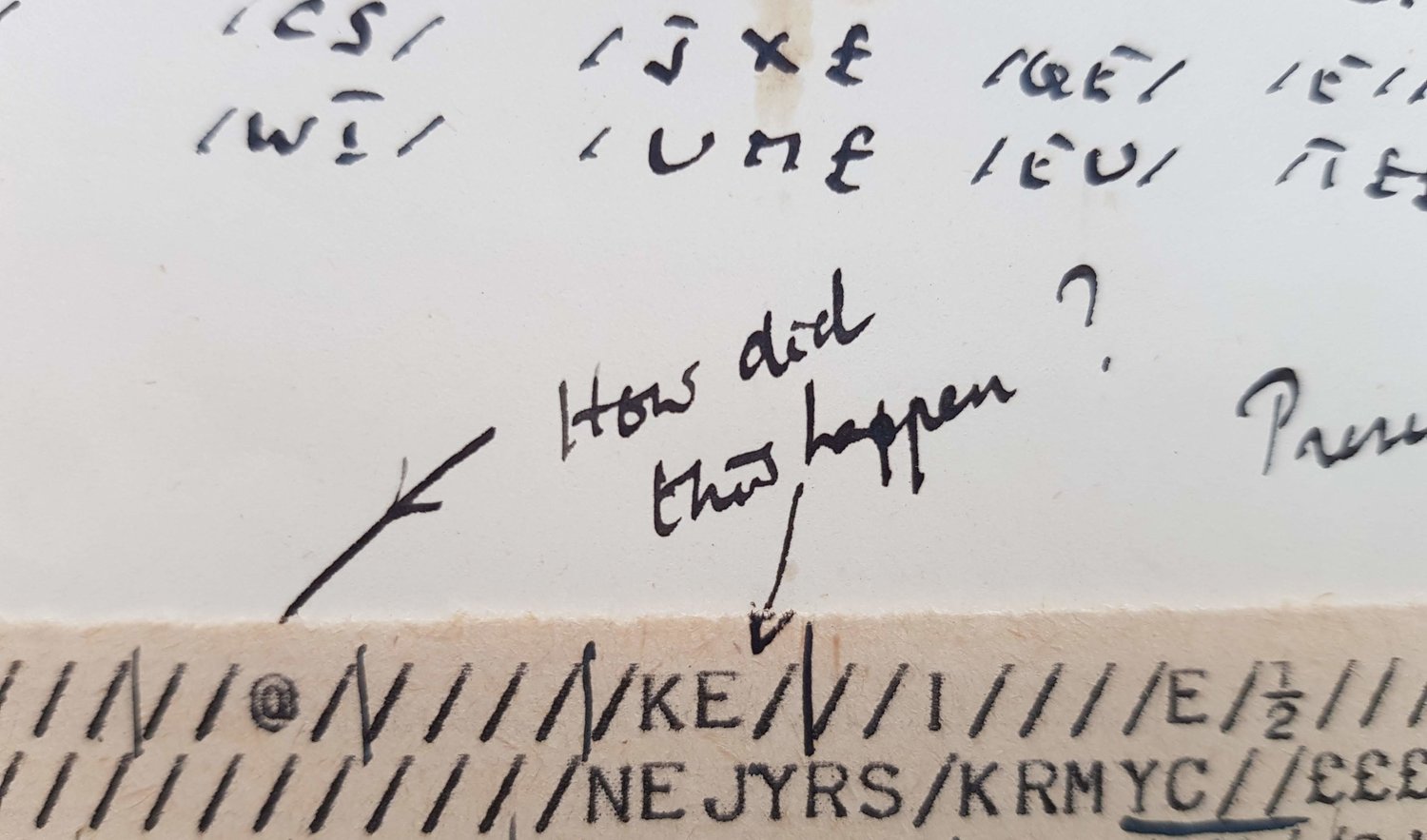

‘Pink scientists’ who were of ‘probable’ interest to the Security Services in 1956. As far as we now know, none ever committed a traitorous act. (c) Crown Copyright, The National Archives KV2 3220 item 306.

Patrick Blackett mainly appears in Alan Turing’s Manchester as a Zelig-y politician, always there in the background to ensure the funds, the brains and the steel were assembled to build the Manchester computer. I couldn’t help but choose a lovely stark studio photograph of him by Lucia Moholy to open a chapter, trying to capture the patrician, urbane, and gorgeous man that people remember, and to mention his family boat, The Red Witch, bought with Nobel Prize money and moored off the Welsh coast where Manchester’s academic families holidayed.

But though I mentioned his MI5 file briefly, I had to leave out quite a lot of what was in its 1152 pages. The file itself was partly declassified in 2010, and has already been pored over by more serious historians than me; Jon Agar’s blog post on Blackett provides an accessible introduction to both the file and why Blackett is of much wider significance than causing Turing to have a job.

What’s most fascinating to me about the file is not the big red ‘SECRET’ stamps all over it, though that surely helps, but the way that the very secrecy allows the kind of character judgements we don’t normally see in print:

Professor BLACKETT is one of the most able scientists in the world, but as with so many geniuses his views on things other than science are often twisted and warped. He undoubtedly suffers from a form of megalomania and is inclined to think that he knows best in all matters.

One irony of this judgement is that it was made by very MI5 officer, Peter Wright, who later decided he definitely knew better than the state when he decided to publish Spycatcher.

Another thing about the file is that it gives us a statistical check on the performance of our security services. In 1956, someone asked them to provide a list of ‘pink scientists’. They responded with a list of nine scientists of ‘probable security interest’. It’s worth remembering that the creators of the list were used to the vocabulary of making important, fast, decisions on the basis of partial information, and that the word ‘probable’ means more likely than not. So of the list of nine scientists, their estimate was that they had found four or five individuals who needed to be actively monitored, if not controlled, to ensure the security of the British state.

Lucia Moholy, Patrick Maynard Stuart Blackett, 1936, shows a relatively young Blackett in the year before he moved to Manchester. Moholy was a documentary photographer who fled from Berlin to London as a political refugee. Decades later she would be acknowledged as the source of many of the photographic negatives that Walter Gropius drew on in his successful postwar mythologizing of Berlin’s Bauhaus, but in the 1930s she had a precarious existence in London. Blackett by this stage was a recognised scientist, and his sitting for her attests to his connections with the intellectual currents of refugee London. (c) DACS 2018 and held in the National Portrait Gallery.

The nine, in addition to Blackett, were Lancelot Hogben, Fred Hoyle, JD Bernal, Kathleen Lonsdale, and Joseph Needham, who I’d heard of for considerable scientific achievement (or popularisation in Hogben’s case); and Munro Fox, Sidnie Manton and Erwin Freundlich, who I had to google. (They also had doubts about Dennis Gabor, but weren’t sure of their identification – if your analysts still have the file open, MI5, he was the guy who was at Imperial inventing the hologram for us). But they sure didn’t get named by Anthony Blunt. As far as I know, in the seventy years since the list was made, not one of these scientists has ever been shown to have done anything that could be called traitorous even by the standards of the time. (Art History turned out to be more productive of traitors). Even, conservatively, taking ‘probable’ to mean probability one half, the probability of getting zero heads when you toss a coin nine times is a bit less than 1 in 500, so Bayesian libertarians would get their all-surveillance-is-bad priors strongly updated by this data. I’m not a libertarian, and I just put ‘Bayesian’ in to keep the consulting fees rolling in, but this is not a good record. I wouldn’t have done any better than they did in 1956 but then I've had nothing to learn from. I ask our Security Services to defend my important freedoms; I allow them the power of surveillance just as I allow the police the power of force. Hitting zero when you claim four is a colossal misjudgement, and acknowledging these past colossal misjudgements would increase, not decrease, my trust that they’re doing the job as best they can.

As usual, this post is by way of advertising my own book, which contains a downloadable list of references, though more conveniently you can find them in Jon Agar’s post; the essential starting point on Blackett is Mary Jo Nye’s biography. (I note on reading Jon’s post that a further misjudgement, in hindsight, was that of George Orwell, who included Blackett in the list of 38 ‘pro Communists’ he sent the government in 1948.)